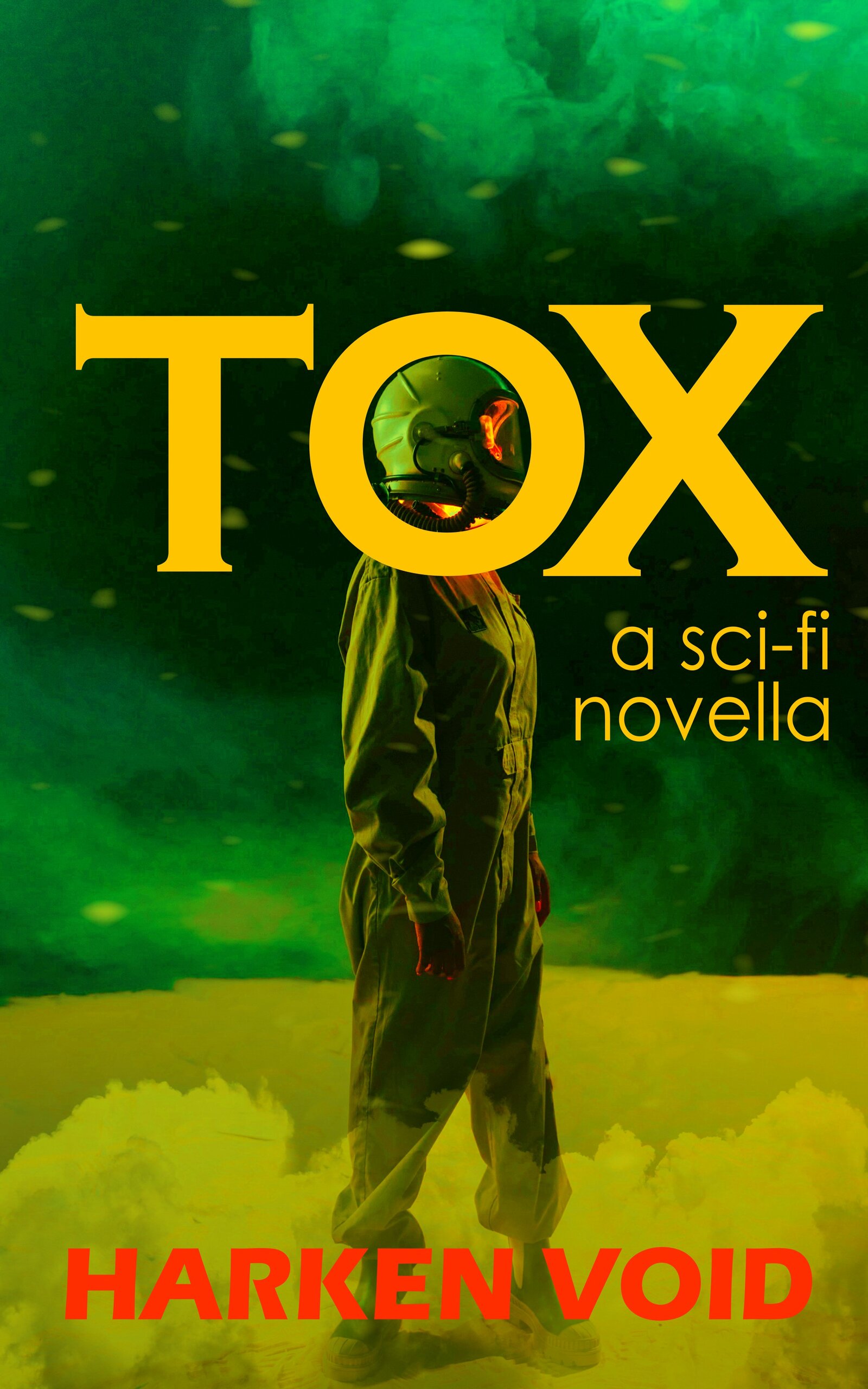

TOX - SAMPLE

Chapter One: The Taste of Iron and Vinegar

As the twenty-ton ceramic door closed shut behind him, and its deep rumble once again settled into a ringing silence, dread engulfed Coghan’s heart. They had left the safety of the Dome. Only Tox awaited them in the wasteland.

He could almost taste the poisonous atmosphere as he breathed the Hellsuit’s filtered air. The helmet’s specs were estimated to be at a ninety-eight point five percent filtration efficiency. Coghan suddenly became very conscious of the remaining one and a half percent.

“Coghan?” Deltrit’s voice came clear through the suit’s coms. The team leader paused and turned, his face hidden behind the helmet’s protective visor. “Something wrong?”

Coghan snorted, composing himself. “Funny question to ask outside the Dome.”

“Fun is extinct on this planet, kid,” Deltrit said. “If you’re not up to this…”

“I am.”

“There’s no shame in turning. I’d rather have a coward and a Hellsuit intact, than a body of a fool, melting in the Tox, and the suit lost.”

Coghan swallowed. “I can take it.”

Deltrit stared at him, as though he could see his face through the reflective surface of the outer visor. The other two Breath Hunters had paused a few feet up ahead, glancing back.

“Alright,” Deltrit finally said. “We’re wasting Breath. Let’s move.”

The man raised his hand and waved at the gate tower, signaling the Dome to secure the airlock. Coghan didn’t dare turn to look at the domed city again. He feared he’d find himself running up the gate and begging to let him in.

Easy now, he told himself. Steady breaths. Don’t waste the filter.

He remembered the training and regained control of his breathing. The air tasted a little of iron and vinegar, but Coghan didn’t let that distract him. He knew the risks of venturing into the wasteland and if he started panicking now…

No, he wouldn’t panic. He and Hixina had a daughter on the way. His family depended on him.

Feeling the weight of responsibility pressing on his shoulders, and the pressure of Tox trying to get into his suit, Coghan took his first step into the desolate wilderness. Once a paradise harboring countless life forms, now a graveyard for over ninety-five percent of all life on Earth.

The chemically scorched soil crunched under his boots like burnt crackers. Visibility was limited to twenty or thirty meters, with a wall of yellow-green fog surrounding everything. Bleached rocks dotted the grey soil and toxic rainwater from the last chemical deluge pooled in bright-red and purple puddles.

“Ah, crap,” Stilpin’s voice came through the coms, jolting Coghan. The man had a somewhat whiney voice, though he was about a full head taller than even Deltrit. And a seasoned Breath Hunter.

“What?” Deltrit barked.

“Damned Tox rain. The way sings are melted.”

“Melted?” Veranda’s voice. Women were rare amongst the Hunters, as usually men would go in their place, but Veranda’s husband was ill with Tox, so she had to provide Breath for their child. “We replaced all the way signs last month.”

“Seems like not even glazed steel can take it.”

Coghan caught up with the others, gathered around a heap of grey dirt. To him, it looked just like the rest of the soil, bleached and degraded, but supposedly the heap was once a block of steel, indicating where to go.

“Damn!” Deltrit said. “That last downpour was more acidic than usual. I wonder if the path is still visible?”

“We’ll have to think of something else to mark the way,” Stilpin said. “You and I might know it by heart, but rookies…” His head turned to Coghan.

“We’ll debate this when we’re back at the Dome,” Deltrit said. “For now, we follow the path. What’s left of it.” The team leader turned to Coghan. “Since you’re last in line, make sure you walk with heavy steps, paving the way. I don’t want our tracks erased behind us by another downpour. If we get lost, we die.”

“Yes, sir,” Coghan said, thankful to the visor for hiding his face. He felt as pale as that dirt.

“Check your power supply and filters again,” Deltrit said. “While we’re still at the Dome. Once we’re in the deep it’ll be too late.”

Coghan looked to the corner of his helmet. The inner side of the visor functioned as a display screen, showing the suit’s status and some basic information about the atmosphere. His suit’s nanobattery pack was at ninety-nine percent and the filter worked optimally.

“Mine’s good,” he said.

“Mine’s good,” Veranda repeated.

Stilpin nodded. “Mine too.”

“Alright then,” Deltrit said. “We’ve wasted enough Breath as it is. Tether up and let’s move out!”

Only now Coghan looked up. Hovering some five meters above their heads was a large blimp, around twenty meters long and five meters wide. Its envelope was made from an incredibly durable material, able to withstand the pressure of a vacuum, which was what kept the blimp in the air. Bags of ballast, filled with the scorched soil of the wasteland, kept it low to the ground. And on its underside, the blimp carried the most precious object in the entire Dome – a Breath canister.

Stilpin and Veranda already wore their harnesses – a thick carbon fiber rope attached to the front of the blimp that split into four equally long strands with harnesses at the end. The idea, as they had explained it to Coghan, was that the team would pull the blimp, adjusting the bags of ballast as they went.

“The blimp is the lifeline of the Dome,” Deltrit said, snatching one strand of the hanging harness and handing it to Coghan. “Without it, it’s all over in a generation. No blimp, no Breath. No Breath, no us. Remember this, kid. Etch it into your heart.”

“No blimp, no Breath,” Coghan said, taking the harness. He put the thing awkwardly over his shoulders and around the waist.

Deltrit watched, then grunted. “You gotta make it tight,” he said, tightening the belt around Coghan’s waist. “You’ll be walking with this for hours. You don’t want any loose jiggling or you’ll risk tearing your Hellsuit.”

“I still think we should use a cart,” Stilpin said. “Yes, we’d need more guys to pull it, but the blimp is so fragile.”

“You can’t pull a full canister over this dirt on wheels,” Deltrit said. “Dirt’s too loose.”

“I don’t like the blimp. I’d prefer a cart.”

“It’d suit you better, too,” Deltrit said, pulling on Coghan’s tether to test it. He patted him on the back and strapped himself in as well. “I read the other day that they used some animal called a mule to pull things in ancient times. Supposedly they weren’t too bright, those mules.”

Stilpin grumbled, but Veranda laughed.

“One more thing,” Deltrit said, turning to Coghan. “To move most efficiently, we walk in sync. Same speed, same stride. As soon as one is out of rhythm with the rest, the tethers work against each other.”

“I understand,” Coghan said.

“You’ll feel it when it happens,” Deltrit said. “Try not to pull us back too much.”

Coghan nodded, feeling the strap holding him a bit too tight. Was he just imagining it or did it obstruct his breathing?

“Stilpin, lead the charge,” Deltrit said. “Start easy for the kid.”

As the three of them moved, Coghan felt the tether pulling him forward. He had to dig his feet into the dirt for the first few steps, but once they overcame the blimp’s inertia, it felt no heavier than a backpack on his shoulders. The blimp’s buoyancy and its ballast kept it in equilibrium.

They walked single-file – Stilpin first, Veranda second, Deltrit third and Coghan last – following faint tracks of what seemed like a trail through the bleached dirt. Coghan trusted these Hunters to know where to go and tried as best he could to memorize the path. If he survived this trip, and many more after it, he knew that one day he’d be leading rookies out into the wasteland, just like they led him now.

If only there was something to orient himself by.

The large city dome disappeared in the thick fog after only a few steps. Without the city’s illumination, the Tox was completely dark. No light penetrated this far down the atmosphere and the team had to turn on their chest-lights to see.

There wasn’t much to see, anyway.

Besides the occasional puddle of sickly colored rainwater, there was nothing else in the landscape. No rocks, no ruins, no grass, no way markings. Just endless grey dirt, cracking under his boots, and puddles of corrosive acid, their thick liquid surface undisturbed by a breeze.

Don’t lag behind, Coghan told himself, keeping pace with the rest of the group. Being tethered, at least he didn’t have to worry about getting separated. There’d be no way he could find them or the Dome in this fog.

The display screen on the inside of his visor showed Coghan the status of his Hellsuit. The suit’s sensors reported deadly levels of toxicity in the air outside – in the Tox – and suggested that he keep the helmet on the whole time.

Yeah. Like he’d want to take it off.

“So, rookie,” Stilpin’s voice came through the coms. “How’s your first day out in the wilds? Feeling sick yet?”

“Don’t upset him further, idiot,” Veranda chided. “Remember your first time? You puked and had to spend the whole trip smelling it.”

Coghan shoved down the sickness in his stomach. Why did they have to remind him? It was his first time breathing raw filtered Tox and the helmet was efficient only to a degree, unlike the Machine Lungs of the Dome.

He tasted vinegar and iron again.

“I remember,” Stilpin said. “And it’s made me respect the wilderness. Made me tougher. I never again lost my breakfast to it.”

“How long have you been doing this?” Coghan asked to shift the attention off of his stomach.

“Breath Hunting?” Stilpin hummed in thought. “Long time. Has to be a year now, right Trit?”

“Eleven months,” Deltrit said.

“Not yet a full year? Damn! I celebrated too soon!”

Eleven months, Coghan thought.

Symptoms of Tox poisoning can occur after mere days of breathing through the Hellsuit’s filters, the Doc had said.

“You celebrated?” Veranda asked. Coghan could hear a rasping to her voice, probably a symptom of the Tox. “What’s there to celebrate?”

“Not being drowned in my own puke, for starters,” Stilpin said. “Not having my Hellsuit leak. Not cracking the helmet, not tearing a hole in the blimp, not being melted by the rain. You know, not dying on one of these Walks. I think that’s cause for celebration enough.”

“I’m not sure about the not dying part,” Veranda said. “I… I’m starting to feel it getting to me. I don’t think I’ll be doing these Walks much longer.”

“This will be your last one, Ver,” Deltrit said.

Veranda paused and turned to Deltrit. “What?”

“I wanted this to wait until we got back, but…” Deltrit sighed. “I know your husband’s been struck with the Tox, badly. You’re starting to show symptoms too, no matter how much you try to hide it. I know you want to continue for the sake of your kid, but what good would it do him if he lost both his parents?”

“Trit, I’m not that sick yet!”

“There’ll be no argument.”

“Trit!”

“Save your filter!”

Veranda grunted in frustration. They continued the somber walk, pulling the blimp silently through the deadly fog. Coghan thought he heard quiet sobs before Veranda’s coms turned to mute with a high-pitched beep.

“Coghan,” Deltrit said after a silence. “Pay close attention to everything you see, hear, or experience. If you’re to learn to survive in the Tox, you have to learn to read the environment.”

Coghan nodded, then realized Deltrit couldn’t see him. “Yes, sir,” he said.

“No need to call me sir. We’re all equal in this. Now look around. What can you tell me?”

Coghan looked to his left and right as they walked. “We’re in dense fog.”

“No shit, genius. What else?”

Coghan checked the ground and remembered that he was supposed to pave the path behind them. “Um… we’re leaving a solid trail behind us…”

“The terrain is rising,” Deltrit said. “Not by much, but it is. See that puddle to the left? If you look closer you’ll see the purple surface of the water is disturbed by tiny strands of red. That means the water’s flowing. Water flows only when there’s a gradient.”

Coghan paused for a moment, trying to spot the water flowing in the puddle. He thought he saw it, then stumbled as the tether tugged him forward.

“Synchronicity,” Deltrit said. “Don’t stop unless we all do. What else can you tell me about the environment?”

Coghan peeled his eyes, not wanting to be the fool a second time. “It feels like the dirt is softer here, sir.”

“Really?” Deltrit pressed with one foot off the path, then continued walking. “Sometimes we want to notice things that aren’t there,” he said. “The wasteland is mostly empty. The same in all directions. Your mind can’t handle blankness and will want to fill it with illusions. And those, Coghan, are more dangerous than even the Tox.”

Coghan blushed, and swallowed a ‘yes sir’.

“Are you paving us a path back there?”

Coghan noticed he forgot again, being too focused on Deltrit’s questions. Flushing further, he stomped his feet harder as he walked.

“No need to overdo it,” Deltrit said. “Your boots aren’t indestructible. Just make enough of a dent so the acid rain will want to flow in that direction, helping us carve a path. Remember, always stay on the path, and always preserve the path. If the path is lost, so are we.”

As if to reinforce his words, the fog thickened around them, lowering visibility to a mere twenty meters or so. The yellow-green Tox rolled in thick whisps as they walked through it, billowing at their feet in small pockets of denser gas. Coghan could swear he tasted that damn vinegar in his mouth each time he passed through such a cloud.

Doc’s words went through his mind, as he observed the dead landscape and kept mindful of thumping his feet, paying attention to the rise of the terrain, and walking in sync with the group. Only the most enduring of organisms can survive in the extreme conditions of our planet, the old scientist would say. And none have been more extreme in Earth’s entire history than the Tox. It’s so poisonous that it dissolves rocks. It breaks water into acid, replaces oxygen and nitrogen in our atmosphere with a toxic cocktail of chemicals that would liquify your entrails should you breathe a single breath of it unfiltered. It killed, we estimate, over ninety-five percent of all Earth life. Only bacteria, and perhaps some moss, can be found outside the Domes.

Ninety-five percent. As Coghan observed the grey dirt, he found Doc’s words to be eerily true. How could anything survive in this desolate hell?

The burden started to feel heavier. Coghan looked up, the dense fog threatening to engulf the entire blimp, which hovered closer to the ground now.

“Path or no path, we’re going the right way,” Stilpin said from the front. “Terrain’s rising.”

“Leak some dirt,” Deltrit said, raising a hand for a pause. “Coghan, watch him. You’ll do it next time.”

Even though the team stood still, the blimp continued gliding forward, tugging on them, until their combined weight stopped it. Stilpin caught the rope ladder that hung from the blimp’s underside and heaved himself up.

“A single man could pull it,” Deltrit said, watching Stilpin climb. “But it wouldn’t be sustainable. You’d burn through the Hellsuit’s filter too quickly. Four people are the sweet spot – enough to share the load, but not too many lives at risk.”

Stilpin reached the blimp’s underside. Two catwalk platforms extended from the Breath canister in the middle and Stilpin used them to reach the ballast bags. He opened a valve on one of the bags and brown sand started pouring out. Coghan moved, not wanting the sand to rain down on him.

“Letting the ballast out is easy,” Deltrit explained. “Filling it up again takes time. That’s why the path we’ve selected has a gradual but constant incline. We only need to release the ballast on the way up.”

“When do we fill it?” Coghan asked.

“When the blimp’s too high off the ground, stretching the tether. But that won’t happen until we start our trip back.”

“I hope you found that interesting, kid,” Stilpin said, “because we’ll be doing a lot of it. Half the Walk is just leaking sand!”

After a minute the blimp rose high enough. Stilpin climbed back down and the team continued walking.

They repeated the procedure every time the blimp began hovering too low to the ground. When Coghan gave it a try he barely managed to climb on the damn thing. The rope ladder swung as he put his weight on it and offered him no stability. He spent five minutes just climbing.

When he finally managed to climb on the catwalk, he leaked too much sand from one bag and not enough from the other, causing the blimp to lean sideways. Luckily Deltrit was paying close attention and stopped Coghan before he’d turn the entire blimp nose down.

They took turns emptying the ballast and Coghan slowly fell in rhythm with the team. Stop the blimp, climb on, leak some sand, climb back down, dig your feet into the sand and heave the blimp forward. Walk for ten minutes, then repeat.

Just like Stilpin said, it took them half as much time to get anywhere due to adjusting the ballast. At least when it wasn’t Coghan’s turn he could use the time to rest. Just breathing through the filter wore him down and there were so many things to keep in mind.

I don’t belong here, he thought. No living thing does.

But someone had to go. The Dome needed Breath and someone had to go get it.

Want to know what happens next?

Find out by buying the book!